I like teaching about science and technology through history’s lens. This approach provides many opportunities to teach across disciplines; history and geography lessons are easily incorporated when instruction, discussion or activities are built around great scientists, inventors and explorers. I’ve found, for example, that it’s nearly impossible to teach the fifth grade Forces and Motion unit labs without introducing Newton and his laws of motion. Where and when did he live? Were there other scientists or inventors working to solve similar problems or answer the same questions at the same time? Where did they live? Sometimes, this instructional strategy can foster student insight into larger lessons about politics, philosophy and human nature.

One effective related tactic is having students imagine life before particular technologies were developed. As a former avid photographer and darkroom enthusiast in the days of film, I have one lesson where I walk students through the picture taking process back in the day, from purchasing and loading film to taking “un-previewable” pictures and dropping film for development and pick up, and paying for processed prints. It’s a story that is fairly easy to tell with great drama when comparing it to the recent convenience of capturing and transferring digital images.

This past Christmas, my sister worked with my father to archive a significant portion of his vast 35mm slide collection onto DVDs. My father was in the Army in the mid to late 1950’s and acquired a Voigtlander rangefinder camera, with a sharp Zeiss lense, at the base PX. He was stationed for a while in Europe, and was able to travel rather extensively through western Europe and across to England and Scotland. In 1958, he was fortunate to be able to visit the World’s Fair in Brussels.

There are a variety of types of World’s Fair Expos, and Brussels had hosted these events on a couple of prior occasions.

Of course, there are often permanent structures associated with various World’s Fairs throughout modern history (Eiffel Tower, Seattle’s Space Needle & New York’s Unisphere), and the 1958 Brussels’ Expo featured the iconic Atomium.

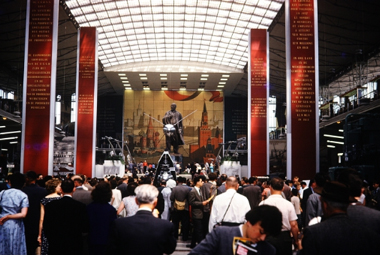

This year will be the sixtieth anniversary of that event. When I asked him about memories, one thing that my dad mentioned was that the Soviet Union’s pavilion had the longest lines.

In the fall of 1957, the Soviets had successfully launched the Sputnik program, with satellites that orbited the earth for weeks before burning up on re-entry. Their pavilion had a model of Sputnik 1 under the watchful gaze of a statue of Lenin.

That event and its associated technology is generally referred to as the official start of the space age, and, as the US and Soviets were locked in a cold war surrounding the development of their respective nuclear arsenals, it certainly signaled the launch of what became known as the space race. These two rival empires, who could barely maintain peace, aggressively competed to develop technologies to conquer the problems of space travel. Every milestone both represented and fueled the cold war. And, by any standard of measure, the Soviets led the space race for exactly one decade.

In December of 1968, the US leapt ahead in this 20th century showdown, when NASA sent Apollo 8 to orbit the moon with three astronauts aboard. The USSR had an unmanned landing and an unmanned orbiter, but America restructured its Moon exploration program and hurriedly sent Jim Lovell, Frank Borman and Bill Anders to circumnavigate our nearest celestial neighbor from an average distance of about 60 miles above the surface (after a nearly quarter million mile journey) for a total of 10 orbits before firing rockets for the return trip. They scoped out potential landing sites for future missions and took the now famous “unscheduled” picture called Earthrise, the first photograph ever of the entire planet Earth viewed from space.

If history reflects an American victory in the Cold War (and it’s probably safe to say that that is the consensus among scholars), this was the first victorious battle. The world will celebrate the 50th anniversary of that event, an event I’m old enough to remember, this December. The generation of students that I teach, while they’ve not had huge and far reaching successes with their space program, should be proud that they are part of the first generation that has never not had people in space. Indeed, the International Space Station, designed by a multi-country consortium that includes the US and Russia and manned since 2000, provides perhaps the most hopeful symbol ever of what countries can accomplish when they can focus on common goals instead of differences.